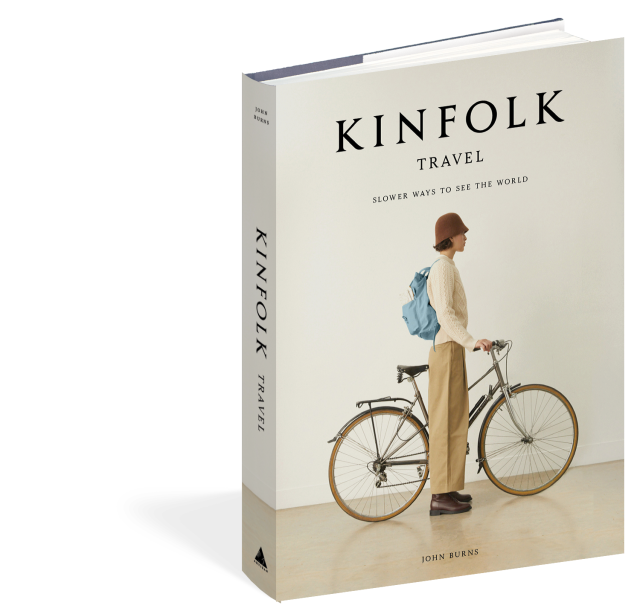

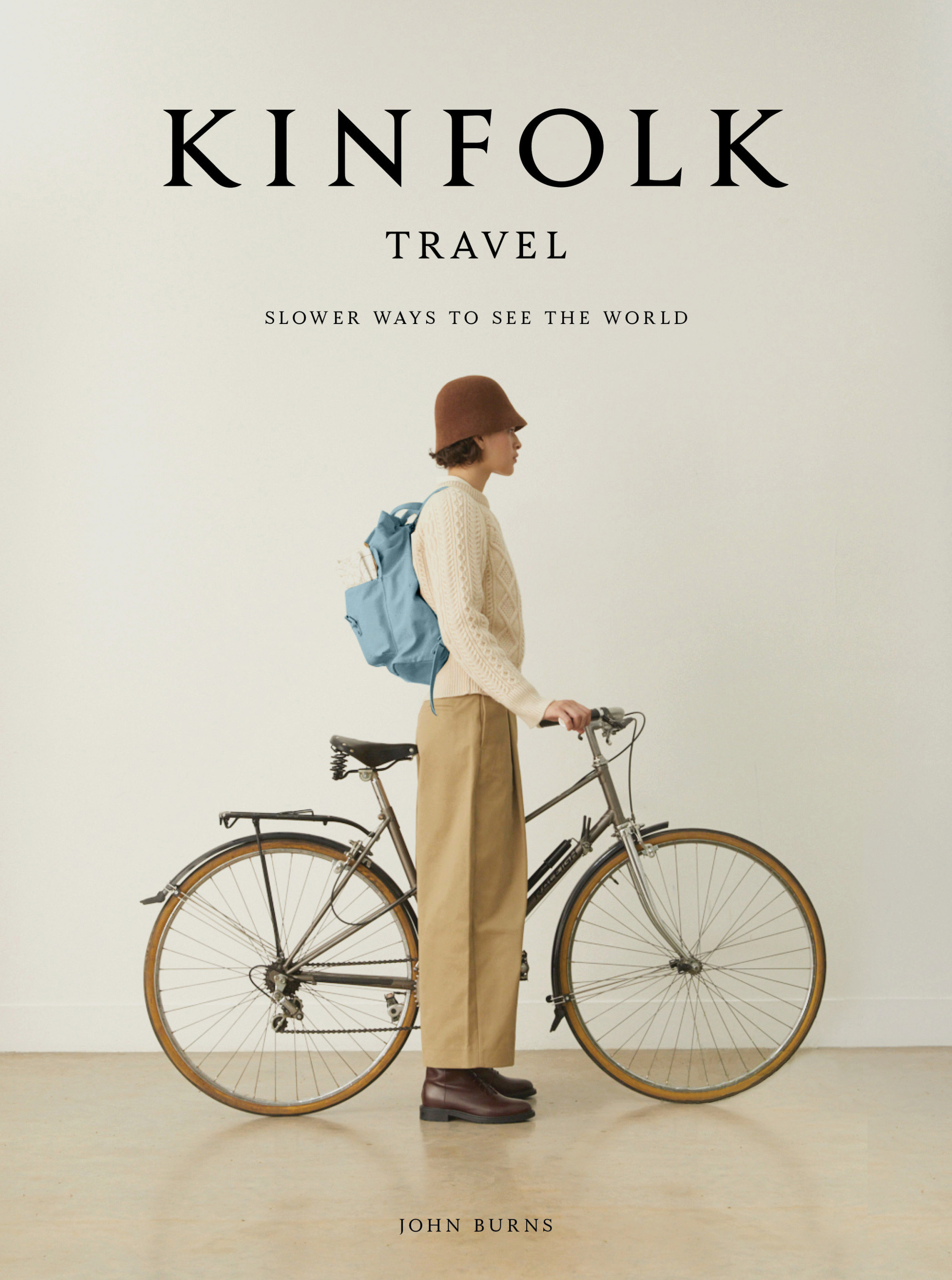

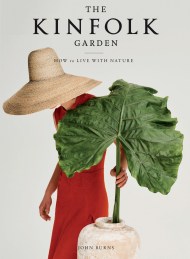

Kinfolk Travel

Slower Ways to See the World

Contributors

By John Burns

Formats and Prices

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

Also available from:

Go museum hopping in Tasmania, or birdwatching in London. Explore the burgeoning fashion community in Dakar. Take a bicycle tour through Idaho, or a train trip from Oslo to Bergen. Drawing on the magazine’s global community of writers and photographers, Kinfolk Travel takes readers to over 20 location across five continents, with travel tips from locals, stunning images, and thoughtful essays.

Series:

- On Sale

- Nov 3, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781648290749

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use