By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

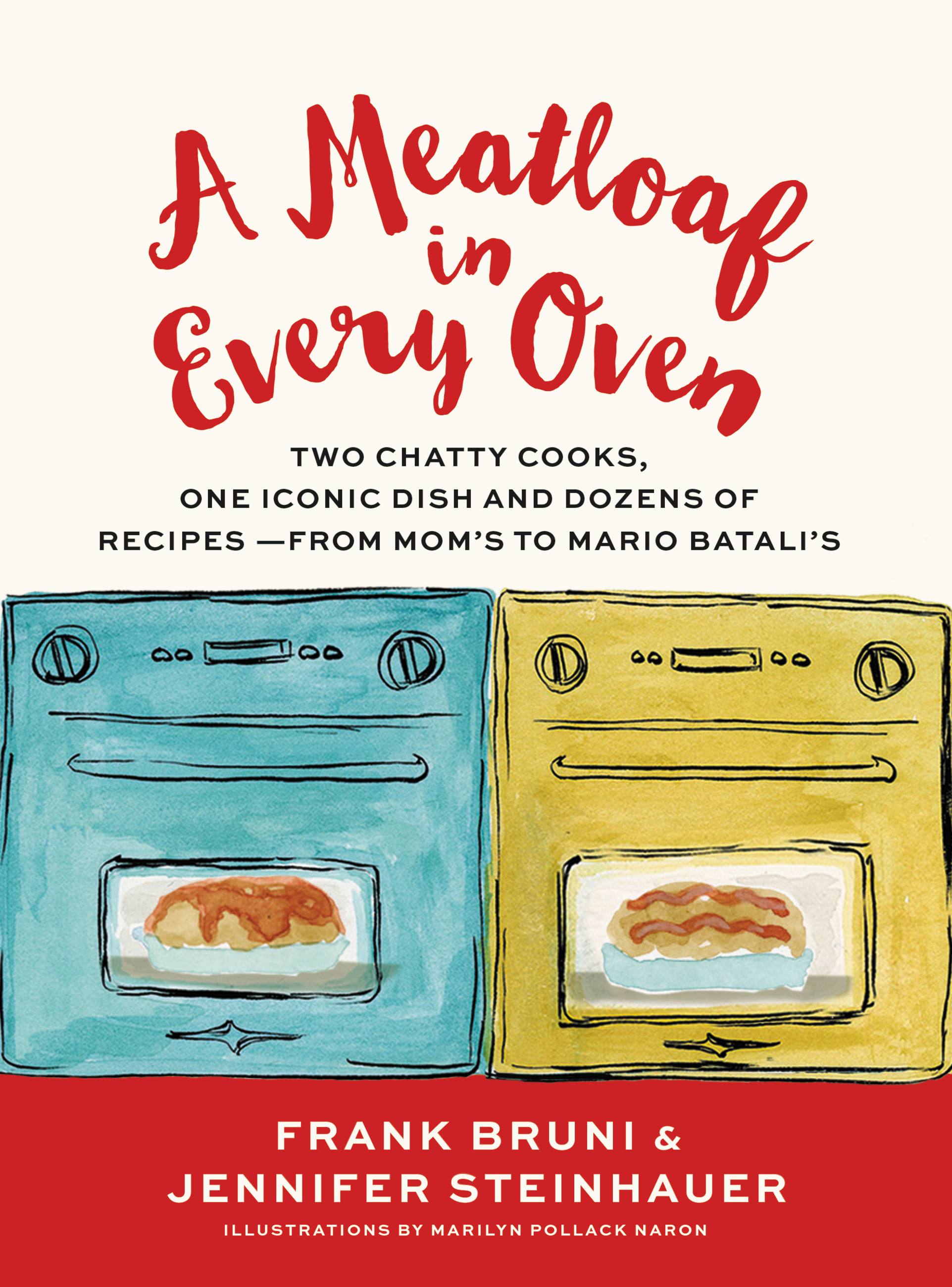

A Meatloaf in Every Oven

Two Chatty Cooks, One Iconic Dish and Dozens of Recipes - from Mom's to Mario Batali's

Contributors

By Frank Bruni

Illustrated by Marilyn Pollack Naron

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $8.99 $11.99 CADAlso available from:

Frank Bruni and Jennifer Steinhauer share a passion for meatloaf and have been exchanging recipes via phone, email, text and instant message for decades. A Meatloaf in Every Oven is their homage to a distinct tradition, with 50 killer recipes, from the best classic takes to riffs by world-famous chefs like Bobby Flay and Mario Batali; from Italian polpettone to Middle Eastern kibbe to curried bobotie; from the authors’ own favorites to those of prominent politicians. Bruni and Steinhauer address all the controversies (Ketchup, or no? Saute the veggies?) surrounding a dish that has legions of enthusiastic disciples and help you to troubleshoot so you never have to suffer a dry loaf again.

This love letter to meatloaf incorporates history, personal anecdotes and even meatloaf sandwiches, all the while making you feel like you’re cooking with two trusted and knowledgeable friends.

Genre:

-

"Liberally peppered with Bruni and Steinhauer's snappy dialogue, this is a terrific collection that deserves a look from meatloaf lovers of all ages."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

- On Sale

- Feb 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455563067

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use